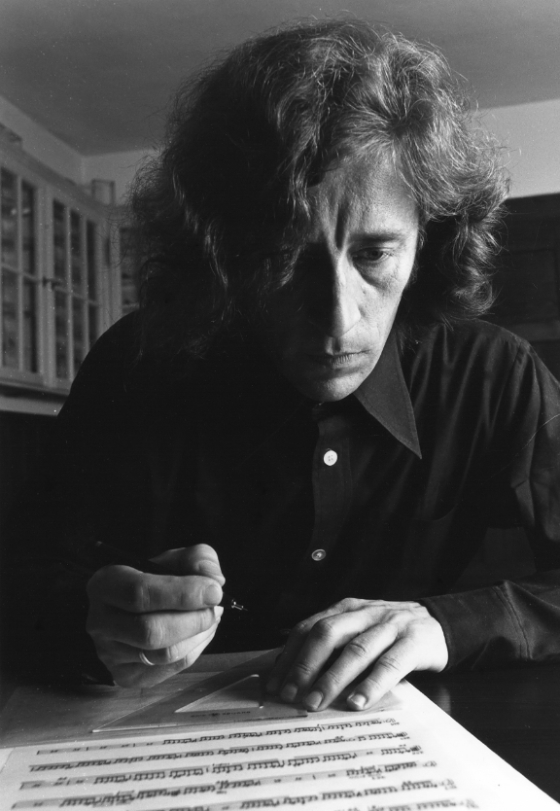

Heinz Winbeck

NAIVITY AND AWARENESS or "The fidgeting in the wheel of time"

- an examination of the conception of music by Johann Heinrich Wackenroders and Theodor W. Adornos -

Lecture on the occasion of the semester opening ceremony of the University of Music Würzburg

on November 7, 1989

Dear students, dear colleagues, ladies, and gentlemen! *

As part of this celebration, newly appointed professors in their specialty introduce themselves: the strings are playing, the winds are blowing, the singer is singing,

... ..

the composer is talking!

Have composers developed into rhetoric specialists, feather foxes, even ideologues in a society in which there is enough talk and writing? Shouldn't your contribution rather counterbalance this? Yes, are they competent at all to perform in an area that is not theirs, that if it were theirs, they might never have become composers? For myself, I can say it anyway, had I even had the "mouth" of an average young person today. What reason would there be to write complex scores if you can bring out everything you want anyway?

Nevertheless, when the composer has to talk, it has nothing to do with a bad re-enactment of someone, even the president of a music academy, but rather the diagnosis of Adorno:

"What is happening musically today has the character of a problem in the undiluted meaning of the word: that of a task to be solved ...".

And since for my predecessor in office, the revered Prof. Bertold Hummel, also in his function as President of this house, the composition class was the icing on the cake at a music college, I would now like to show my colors, albeit one year late, which salt I intend to use. Pious Jews have a custom of Pascha: they take a sip of saltwater in memory of the tears of exile and forced labor - you, who sit in front of me and are used to good Franconian wine, take it in your spirit, symbolically, anyway Take a sip to be prepared for future injustice.

At the beginning of my speech, I would like to pick up on another one that many of you have probably heard: the acceptance speech given by Maximilian Schell by Vaclav Havel on the occasion of the award of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade on October 15 in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt on the MACHT DES WORTES. Far be it from me to want to continue this impressive speech, but since it still rings in our ears, I would like to ask you whether you could imagine anything remotely comparable in translation into the language of music? It was about the charisma of linguistic terms that set entire generations in motion, their ambivalent nature as a “flash of light” as well as an “arrow of death”, about those responsible for morality, i.e. this reflective speaking, even about "arrogance" and "humility" of terms ... Strange, no one would think of speaking about music in this clear and authoritative manner, despite all the - not least economic power of the music business; And yet we feel, if we are honest, that there is something comparable here, too, despite all the differences in language, only masked by a supermarket of possibilities, some of which seem to be more oriented towards advice from skilled sales strategists than to considerations regarding " Arrogance ”or“ humility ”of a sound, a composition.

This path of thought inevitably leads us to the basic question: What criteria was and is the musical work of art committed? Does man seek in himself or possibly the correction of his being, even the redemption of himself? And how did it get to the point where someone with a knowing smile at the sound of some “discord” would surely state: Aha - a new speaker!

In my search for material, while studying, I came across not only the relevant works by Busoni, Stravinsky, Henze, etc., but also wise words notoriously accompanying music festivals by musicologists and composers - e.g. on the controversial terms “avant-garde” and “postmodern” on the occasion of “revolution in music” in Kassel - rarely gold. Of course, the apocalyptic siren chants by Heinz-Klaus Metzger, for example, make one think: “... composing as a certain negation would be ... the abolition of everything that was ever understood as music. Because in the face of the industrially produced end of the world, only music that is no longer music is still music; while the music that is still music is no longer music. "

What is rising from the memory of the 70s? “There is no God who exists.” While I can understand this sentence as an attempt to express a negative theology, I remain suspicious of “negative musicology”. Gradually I liked it best, like Heinz Holliger, regretting that older composers had remained “mute as fish”, Holderlin quotes: “The quieter, the more utterance”, so that Heinz Winbeck, quoting Heinz Holliger, who said Hölderlin “ The quieter, the more utterance ”quoted, with which the speech that has barely begun could also end immediately!

But since this would hardly be in the sense of this event, if it would also bring joy to one or the other audience, let me now turn to the two authors with whom I found what I was looking for and who only at first glance have nothing to do with each other seem to have: one, Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, spiritual pioneer of early romanticism, the other, Theodor W. Adorno of the 68 student rebellion!

I begin with Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder's conception of music, whose life from 1773 to 1798 lasted barely 25 years. He illustrated this in an essay entitled “Of two wonderful languages and their mysterious power”, in the music novella “The strange musical life of the Tonkünstler Joseph Berglinger”, but also in a small, peculiarly modern-looking “Wonderful fairy tale of a naked saint”. Why modern? For this "saint", of whom Wackenroder himself says that we would consider him insane, but that the Orientals would consider him "the strange container of a higher genius", the phenomenon of time is no longer a matter of course, but:

“During his stay, this strange creature had no rest day and night, it always seemed to him that he heard incessantly in his ears the wheel of time making its whirling turn. He could not do anything in front of the din, undertake nothing, the tremendous fear that strained him in perpetual work prevented him from seeing and hearing anything, other than how the terrible wheel turned with a roar, with a tremendous rush of storm winds, and then turned again, that reached up to the stars and across. Like a waterfall of a thousand and a thousand roaring streams that tumbled down from the sky, pouring themselves eternally, eternally without a momentary standstill, without the calm of a second, so it rang in his ears, and all his senses were mightily turned only to his working Fear was more and more gripped and torn into the vortex of wild confusion, the monotonous tones became more and more wildly confused: he could not rest now, but one saw him day and night in the most strenuous, violent movement, like a person who tries is to turn a tremendous wheel. From his broken, wild speech we learned that he felt drawn away from the wheel, that he wanted to help the raging, lightning-fast turnaround with all the effort of his body, so that time would not run the risk of standing still for just a moment. When asked what he was doing, he would scream the words out in a convulsion: You unfortunate ones! don't you hear the rustling wheel of time? and then he turned and worked even harder again so that his sweat flowed to the ground, and with contorted gestures, he laid his hand on his beating heart, as if he wanted to feel whether the great mechanism was in its eternal motion."

Ladies and gentlemen, if the length of the quote has given you the terrible suspicion that the condition of this deplorable person has anything to do with the state of mind of us composers, then you are correct! I only ask you, my dear listeners: why is this man, of whom it is said a little later that he can also be dangerous, not put into custody? I can only guess the answer: because the reverent observer senses within them that he does not hear this “wheel of time”, whose “roaring change” they do, but turns for them, that his “working fear” is also knocking hidden inside them and that something falls away for them too if he goes through this strange struggle. This does not succeed at first, the moonlit night, i.e. the natural mood of all dissolved boundaries, only brings a temporary calm and an all the worse relapse:

"... when the moon suddenly stepped in front of the opening of its dark cave, it suddenly stopped, sank to the ground, tossed around and whined in despair; He also wept bitterly like a child that the sound of the mighty wheel of time would not leave him in peace to do anything, to act, to work and to create on earth. Then he felt a consuming longing for unknown beautiful things; he tried to sit up and move his hands and feet gently and calmly, but to no avail! He was looking for something specific, unknown, something he wanted to grasp and to cling to; he wanted to save himself outside or inside himself but in vain! His weeping and his despair rose to the highest, with a loud roar he jumped up from the earth and turned the mighty, whizzing wheel of time again. "

The sufferings of this man only come to an end when two new components condense and transform the mere natural mood: give it a face in human love and sound in human song. The liberated genius of the poor naked transforms and rises to the sounding spheres: "Traveling caravans were amazed to see the nocturnal miracle apparition, and the lovers imagined they saw the genius of the love of music."

"Love and music" - the escapist utopia of the so-called. The youth culture of the 20th century, which as perhaps the most successful “half or pseudo-ideology” after the West is now also flooding the East: is that what Wackenroder meant? Hardly likely. His 'Joseph Berglinger' is the progenitor of all composer figures in German literature up to 'Adrian Leverkühn' - alias Nietzsche-Schönberg - on whose figure Adorno, as is well known, worked hard during the emigration in Los Angeles! I do not need to go into more detail here on the fact that Thomas Mann did not form the figure of the lonely struggling composer as a symbolic figure of German tragedy and Demonia by chance. In any case, Wackenroder's comparatively simple title figure proves through its failure that neither a pleasurable, primitive stomping along with the wheel of time, be it according to Discomanier, nor a rescue in an allegedly intact subscription concert redemption world is an option for him as a composer. In his downfall, however, it becomes clear - and with this dialectic, we are already very close to Adorno - that a third thing must be kept open beyond the "easy" paths.

So why does this young composer fail? He, who comes out of the tightness of typically North German eighteenth-century conditions characterized only by the mandatory term, initially finds an immeasurable widening of horizons and feelings in the world of music by moving to an “episcopal residence” in the south. But the problem arises from a kind of life balance in the form of a farewell letter, a razor-sharp self-analysis of the person who, like his author, died prematurely. The three states of tension that he cannot resolve are:

1. the discrepancy between "SENSATION" and "MECHANICS", a tension of opposites that we today probably adequately represent with the terms NAIVITY AND CONSCIOUSNESS. The young composer describes the main problem of his studies as follows:

“When I think back to the dreams of my youth, how blissful I was in those dreams! - I said I wanted to keep fantasizing about and let my heart out in works of art, - but how strange and bitter the first years of an apprenticeship came to me! How I felt when I stepped behind the curtain! That all melodies (they had also produced the most heterogeneous and often the most wonderful sensations in me) were now all based on a single, compelling mathematical law! That instead of flying free, I first had to learn to climb around in the awkward scaffolding and cage of art grammar! How I had to torment myself, first with the common scientific understanding of machines, to bring out a real thing before I could think of handling my feelings with the tones! - It was a laborious mechanism."

2. The discrepancy between ART AND SOCIETY. I think it will not be difficult for you to translate the experiences of our protagonist into a present in which what is described here has only, on the one hand, become colossal, shifted, or hidden on the other:

“What happy hours I enjoyed as a boy in the large concert hall! When I sat quietly and unnoticed in a corner, and all the splendor and magnificence enchanted me, and I so ardently wish that these listeners would one day gather for the sake of my works and give their feelings to me! - Now I often sit in this very room and also perform my works, but I feel very different. - That I could imagine that this audience, strutting in gold and silk, would come together to enjoy a work of art, to warm their hearts, to offer their feelings to the artist! ... Of course, the thought is a little comforting that perhaps in some small corner of Germany, where this or that from my hand comes, even if long after my death, there lives another person in whom heaven has such sympathy put to my soul that he can feel from my melodies exactly what I felt when I was writing it down, and what I wanted so much to put into it. A nice idea with which you can be pleasantly mistaken for a while! - The most horrible things are all the other relationships in which the artist is knitted. Of all the disgusting jealousy and malicious demeanor, of all of the petty customs and encounters, of all of the subordination of art to the will of the court; - I resist speaking a word about it - it's all so unworthy and the human soul so degrading that I can't bring a syllable of it across my tongue. A threefold misfortune for music that this art requires so many hands for the work to exist! I gather and lift all my soul to do great work; - and a hundred numb and empty heads are talking, demanding this and that. "

However, it is by no means the glorification of a lonely artistic personality at the expense of so-called “ordinary” people that Wackenroder strives for, on the contrary, Berglinger suffers no less from the “bloatedness” of successful colleagues and asserts: “Truly, art is what you revere must, not the artist. ”This“ weak instrument ”ultimately gets the fatal blow from the third, bitterest of all antinomies:

3. the between ART AND MORAL or RESPONSIBILITY in the human area. On the deathbed of his father, who in vain would have wanted to turn his son into a helper for humanity and something sensible, a doctor, given the depraved siblings whom he has more or less left to their fate, his life energy experiences a bloodletting from which he does not more recovered. But he stretches out for one last effort:

“He was supposed to make new passion music for the upcoming Easter, which his jealous rivals were very eager for. But bright rivers of tears broke out from him whenever he wanted to sit down to work; he could not save himself from his torn heart. It lay deeply depressed and buried under the slag of this earth. At last, he tore himself open with violence, and stretched his arms up to heaven with the hottest desire; he filled his mind with the highest poetry, with loud, exultant singing, and wrote down with wonderful enthusiasm, but always with violent emotions, a piece of passion music, which with its penetrating melodies and all the pains of suffering in itself forever will remain a masterpiece. His soul was like a sick person who, in a wonderful paroxysm, shows greater strength than a healthy person. But after he had performed the oratorio on a holy day in the cathedral with the greatest tension and heat, he felt quite weak and slack. A nervous weakness attacked all its fibers like a bad rope; - he was ailing for a while and died not long afterward in the prime of his years."

I have little more to add to Wackenroder's words. You must have understood why I gave you so much space: we find it difficult today to express these relationships so naturally and precisely, so “naively” and “consciously”. I would just like to ask the question: Is that why we have been looking at the romantic ideal of art as dead for some time, putting it aside with a cynical, compassionate smile because we believe we are escaping the antinomies outlined here? But if these are not fundamentally connected with the human condition, so that avoiding it would mean that the artist becomes an autistic player who, with the help of his elbows, has managed to occupy a few meters on the playground of the cultural industry for his self-expression? What connection exists between this exposure, this image of a man and the level, the quality of the music that was created during this time?

So that you don't believe that a wistful retrospective is being spoken here, we now turn to the Alban Berg student, composer, music theorist, philosopher, and most prominent representative of the so-called "Frankfurt School", which is known to be a critical reality in the Federal Republic of Germany Subject to analysis, Theodor W. Adorno. For right-wing circles, his name was until recently the literal “red cloth”, a synonym for all the dangers associated with the word “overthrow”. The revolutionary students he woke up could only shake their heads at their teacher when, using an Eichendorff poem, for example, he tried to defend his concept of art against this new variant of cultural barbarism. Interestingly, even today - 20 years after Adorno's death, his name is particularly popular as a bone of contention - I am not so sure whether those who prefer to refer to him would also be recognized by him as his "heirs". But make your picture, I would like to allow you to do so. Let me just add a variant of the answer to the question “Who was Theodor W. Adorno?” which I am sure you will not find in a feature section because I have seen it myself:

On the occasion of a trip to Vienna in the mid-1970s, I gathered all my courage and together with my wife visited the 86-year-old widow Alban Bergs, Hietzing, Trauttmannsdorffgasse 27, who was still alive at that time to blame for everything, but for Frau Helene Berg the world came to a standstill with the last stroke of the pen from her husband. We stood reverently in front of Alban Berg's wing, on which the beautiful old woman had stacked all the books that had been written about Alban Berg when my wife saw the Adorno writings and asked in the silence: "Can you still remember Adorno?". Then the answer came promptly: "No, of course - you can't read it - but - a nice boy!". (Should the old woman have recognized her husband's disciple better than all the right and left together?).

But let's start now with his "Criteria of New Music", an essay that is hard to believe is thirty-two years old again! Judge for yourself to what extent it (also) today - or perhaps even more so today, is a cornerstone that anyone who makes it too easy for themselves will bump into. NAIVITY AND CONSCIOUSNESS or FIDDLING IN THE WHEEL OF TIME The fear of the blank sheet. "Everything that you have written yourself would be written differently after a week." Said Proust in "In Search of Lost Time" and Tolstoy: "The writer must have some childish simplicity, the naive courage of a child, to take a step to say something loudly and audibly, without fear of saying the wrong thing. “He's right! But Adorno: "... [music], wherever it is to be taken seriously, [has] broken the naive relationship to a given material." He is right!

Do you know this one?

Two opponents at war with one another present their point of view to the rabbi one after the other; the rabbi listens to everything calmly and then first agrees with one and then with the other. Does the woman, who has been listening at the door, to her husband: “How can you say to the one“ you are right ”and also to the other?” The rabbi looks at his wife for a long time and finally says “Wife, you too are Law!".

He is right (whom his wife considers meshuga), the antinomy between naivety and consciousness cannot be resolved, at best it can be endured. Adorno: “You don't intellectualize music if you consciously face it” and “You can't ignore the level of consciousness of the epoch.” Adorno himself spoke of both the “philosophy of the child's gaze” and “What a child feels that is Fresh snow leaves its footprint is one of the most powerful aesthetic driving forces ”as well as the indispensability that the work of art has to face the undisguised sadness of our time and what shaped it. Fascism, in which the “alb of childhood” has come to itself, Stalinism as a perversion of a political utopia, “damaged life”, the permanent damage to life in a mass society built on overexploitation: a piece of music that doesn’t hear the cry of it contains, it will never achieve "the breakthrough to the completely different". It was precisely his Jewish-messianic legacy that forbade Adorno to make comparisons with history - but this is known to have gone out of fashion in postmodernism and posthistoire; and with it the claim of the work of art to change something in the “hic et nunc”: Sugar is in demand again, not salt; where the “critical unconventional outfit” has long been part of the styling.

How would Adorno, who rode his whole life against the commodity character of art, have felt in a postmodern age that unashamedly pays homage to it, understands history as a supermarket, disregards everything, allows everything but at the same time undermines the irreplaceability of art itself?

What would he have said about a new concert series started in Munich, to which - to the surprise of the two interpreters - the following program was invited: Franz Schubert: 5 songs based on texts by Walter Scott

Franz Schubert: 4 songs based on Johann Gabriel Seidl

Robert Schumann: 12 poems by Justinus KernerCarpaccio from brook trout with roasted sesame

Soup with porcini mushrooms

Venison with parsley sauce on gentian sauce, broccoli, and potato noodles ...

... I'll break off here, but don't forget to remember the inclusive price of DM 85 and the requested evening wear.

But, ladies and gentlemen, what do these noodles mean in comparison with the fact that the largest amounts of money for music festivals and projects these days are often made loose by large corporations that directly or indirectly support armaments businesses - in plain English So from wars and murders in the third world - earn? Should the so sponsored composer be paid with “blood money”, or should he forego performance opportunities, or should he be happy if he is foregone?

Wouldn't it be more desirable for New Music to come closer to people again so that it would not even be dependent on this kind of support? Since this, if one excludes audience-oriented composing, which I take for granted, of course, amounts to an educational question, I would like to take this opportunity to expressly thank the music teacher from Lohr am Main, through whose initiative my students in the past semester were extremely happy and with were able to do grassroots work in the province.

In contrast to this, is it not downright sad to see how young people from the East and West fraternize under the sign of rock music that represents freedom and a democratic attitude towards life for all, writers and actors contribute their bit, but none of them even contribute to their contemporary presence? Russian music in this spectrum seems to ask? Doesn't that also affect us that on the one hand, we keep institutions running - a music academy also includes composition students - but on the other hand - hand on heart - how great is your curiosity, your expectations, and also your willingness to help really concerning the question: how Can one, not disregarding the level of consciousness of the epoch, still compose today, or even compose even more?

"Yes, if it is good ..." you will think to yourself, not realizing that your fertile or sterile expectations alone contribute to the quality of the composition, because after all, art - according to Adorno - is the floating phenomenon not only between the societal one's Constraints and the ideal of freedom inherent in all of us,

So Adorno says, referring to Kant's demarcation of aesthetic judgment from taste judgment: "... judgment is made as if in the dark and nevertheless with a well-founded awareness of objectivity.", With the "experience of necessity that gradually imposes itself ...", an " infinitely delicate and fragile logic, just one of the tendencies, no tangible norms for what should and shouldn't be done."

Adorno tries to capture this dialectic between freedom and necessity in ever new captivating formulations. For him, the phase of “free atonality” around 1910 is still the “heroic phase of new music” before it was solidified in the twenties in Schönberg's 12-tone technique on the one hand and the neoclassicism of Stravinsky on the other. Since this necessity has to do with objectivity, but nothing to do with given abstract norms, and rather results from the respective prerequisites of the work itself, it is extremely difficult to define. But what appears here perhaps only as a language problem means practice, the daily bread of the composition lesson. The concept of compositional clarity seems helpful to me here: “Works of art are the deeper, the purer they express the contradictions of their approach, their own possibilities.” “Today, however, compositional power is that which abandons itself to full differentiation and yet it is theirs himself, like one who remains mighty to unity. "

"But the ambiguous must also be clearly 'composed out'; ..." and "All of this revolves around the concept of musical internal tension and its slackening ...". In athematic music, too, “the relationship between now and then must not be coincidental ... It is likely that a major factor here is whether developments are 'composed out': that is, whether categories such as consequence, antithesis, fresh approach, transition, dissolution become comprehensible as such, to appearance Find; ... "In music itself, memory and expectation are integral moments of its presence. "

This position of Adorno, which is binding for me, is by no means for contemporary music as a whole - on the contrary - here, as expected, opinions differ. John Cage, for example: “Every moment shows what is happening. How different this sense of form is from that which is bound to memory ... "

Yes, how different! Adorno already suspected that "all so-called static music ... is apparent" and finds its "real reason" in "not facing the passing of time and its horror." To give up the siren songs, the principle of development in music - “A mere change is not development.” - Sometimes one cannot help but suspect that they sound all the louder when virtue is made out of necessity.

Of course, the eloquent Adorno also finds it easier to formulate how New Music should not be, what he recognizes as a mistake than the opposite. And he's not alone in that. Whether you see it as an equivalent to negative theology or just an explanation for the frequent tension between composers - which does not apply to this house - is up to you! But perhaps this fact, which is often rather unpleasant in practice, also has its positive side, perhaps it is more than just turf wars between top dogs fighting with their backs to the wall. In any case, Adorno had little in mind with impartial, slack tolerance when he said: “The present diversity, however, is not that of wealth… but one of disparate. ... Such wealth is wrong and he has to resist the consciousness not to run after him. "

He also speaks quite openly of infantilism as the danger of a frozen avant-garde, of the fact that artistically what can be correct in terms of material does not have to be coherent. He also sees the temptation to get lost in technological gadgets: “Thanks to the technical work that has congealed in them, pre-artistic structures can create the impression of extreme sublimation. They are based on a primitive view of science and art. ”… Neither“ the more science and technology advances, ”…“ can retreat to the world… pure feeling ”, nor can the work of art become“ through the adoption of technological procedures ” aesthetically guaranteed ... "

This seems more relevant today than ever. And if it is far from my intention to break the baton over all these manifestations of homosexuality, I at least dare to ask the question of whether contemporary music is not becoming an appendage of the computer industry in a highly adapted way? It is always about a very harmonious marriage between various mammoth corporations and the composers who are considered "well-known" by their culture managers and - as Adorno said: - "... today someone quickly becomes ... from avant-garde to a salon composer."

The often not even half-educated music criticism also contributes to this, of course, whose disproportion between claim and ability Adorno would certainly not judge more indulgently than thirty years ago when he wrote: “The current confusion of musical judgment is not only based on tradition -loss and specialization that allows understanding even among so-called experts in ever smaller numbers, but also in the fact that in the chaotic music business works are compared and weighed against each other without their level of the form being asked."

Yes, the fidgeting in the wheel of time can take on strange forms.

In which direction I could imagine a fruitful collaboration between science and art, I can only indicate here. Hoimar von Dithfurth a week ago. Ditfurth, to whom I owe a lot as someone who has always looked beyond the boundaries of his numerous specialist areas. For example, the composer is able to give impetus to what he explains in his penultimate book "So let's plant an apple tree - It's so far" about the non-monistic, non-exclusively materially derivable nature of the brain or the capacity for consciousness To teach us to see anew the immaterial trace that life leaves. Isn't it instructive when the natural scientist parallels the difference between brain and consciousness with the familiar fact that instruments, no matter how highly developed and mastered with virtuosity, do not produce a composition in themselves, but rather the composition as a creative act presupposes this? In this context, Ditfurth quotes the beautiful Schopenhauer word: "Because in death, however, consciousness is lost, but by no means that which had produced the same up to then."

It seems to me that this is not a flight into only apparently higher spheres that turn out to be illusory, but elevation into an existence that is actually hidden behind all foregrounds, which fascinates the natural scientist as much as the musician.

Perhaps to some of you, the word “loss of tradition” in Adorno's mouth seemed unexpectedly conservative, but in fact, in his view, the music-language tradition is “as little to preserve as to throw overboard, but to transform ...” with the same dialectical one Thinking figure of the ABOLITION in the threefold sense of the word (denial of the epigone - storage of the valuable - elevation in the transformed context) he approaches the elementary, the European music history moving basic concepts: EXPRESSION - INVENTORY - OWN SOUND. "Where such a tone would be puristically expelled, the best would be forgotten." Contrastitat, Heiner Goebbels: "The time for personal styles is over." Adorno: "... with the composer's flourishes: a kind of second-degree conformism: one qualifies by disposing of them a limited number of modernist vocabulary as belonging to it, as someone who is able to speak the new language, and that is precisely why one speaks it incorrectly. "

I confess that one of my main concerns in class is to get to grips with this second-degree conformism, and although it makes everything much more difficult, I am happy to be able to say after a year that my students - each of them to their own best Wise - are willing to go along this arduous path between Scylla and Charybdis and give me many suggestions on this hike.

Even the worn but irreplaceable terms such as SENSE, SPIRIT, MORAL of the work of art, its BEAUTY, and its LUCK belong in this series. I'm afraid I would (really) overstrain your patience if I analytically analyze each of them, and the scales, the two shells of which are called NAIVITY and CONSCIOUSNESS, would finally sag to the second side.

So at the end of our common journey with Adorno, let me just put a few more sentences on the above terms in their inimitable linguistic conciseness without comment:

“Those dissonant chords, on which the anger of the normal consciousness conspired to disaster once ignited, ... were carriers of the expression not only of pain but also of pleasure.” “The multi-tone sounds not only hurt but were always in their cutting brokenness at the same time beautiful. "The moral of the work of art, not to be owed, wants to honor the change that the first bar signs. "This happiness ..., drawn together at the point of being able to say the terrible at all ... "Would be even the new music is nothing more than an expression of that despair before the world; it would already be more than that by expressing it. "

Thank you for dedicating an hour of your time to me and I close with a little dialogue between Kublai Khan and Marco Polo from Italo Calvino's “The Invisible Cities”, which - I think - is our ultimate goal for all of us all journey through time has to say:

Kublai Khan:

“Everything is in vain if the last landing stage can only be the hell city and the current pulls us down there in an ever-narrowing spiral.” And Polo: “The hell of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is the one that is already there, the hell in which we live every day, which we form through our being together. There are two ways of not suffering from it. One is very easy for many: accept hell and become part of it so much that you no longer recognize it. The other is daring and requires constant caution and attention: to seek and to know who and what in the middle of hell is not hell, and to give it continuity and space. "

© by Gerhilde Winbeck

* Notes on this edition: The template was the typescript of the speech, it is handwritten

Corrections and insertions appear here incorporated. Obvious typographical errors were tacitly corrected. In the PDF version, which is available for download here, underlining has been retained and blocked text parts are shown in italics. In addition, findable sources of quotations were added as endnotes.

[Hermann Beyer]

Translation by Daniel Hensel